Schädelfraktur

Skull fractures are common in the setting of both closed traumatic brain injury and penetrating brain injury. Their importance is both as a marker of the severity of trauma and because they are, depending on location, associated with a variety of soft tissue injuries.

This article will focus on a general terminology of fractures and delegate discussion of particular fracture patterns to separate articles (e.g. base of skull fractures). Facial fractures are also discussed separately.

Terminology

Skull fractures can be broadly divided in a variety of way:

- anatomically

- base of skull

- skull vault

- associated with overlying wound

- open (compound)

- closed

- degree of displacement

- undisplaced

- depressed (5-10 mm)

- number of fracture lines/fragments

- linear

- comminuted

Pathology

Fractures of the skull, as with fractures of any bone, occur when biomechanical stresses exceed the bone's tolerance. The pattern of fracturing depends on the location, direction and kinetic properties of the impact as well as intrinsic features of the skull .

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

Plain radiographs have a limited role and are superseded by CT scans. They are no longer recommended to assess head injuries unless as part of a skeletal survey for a suspected non-accidental injury of a child .

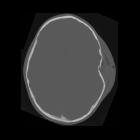

CT

Skull fractures are best imaged with CT of the brain. Not only is CT sensitive to the detection fractures but it is also able to exquisitely characterize their extent and allow for surgical planning. Furthermore, it is obtained at the same time as the brain is imaged.

CT of the skull should be obtained volumetrically with small (<1 mm) voxels and be able to be reconstructed in multiple planes. It is essential that a bone algorithm is used if undisplaced fractures are to be visualized.

Fractures will appear as discontinuities in the bone and may or may not be displaced. They need to be distinguished from normal sutures, which have corticated margins that fractures lack. Almost invariably, if the fracture involves a paranasal sinus, middle ear or mastoid air cells, then they will contain some blood, which is a helpful clue to the presence of an underlying fracture.

When a fracture is identified, a careful search for adjacent soft tissue injury should be undertaken. Examples of soft tissue injuries include:

- vascular

- arterial dissection, occlusion or rupture

- arteriovenous fistula (e.g. direct caroticocavernous fistula)

- dural venous sinus injury

- extension through cranial nerve foramina or canals with neural damage

- underlying cerebral hemorrhagic contusions

- dural tears leading to CSF leak and intracranial hypotension

MRI

MRI is insensitive to fractures and it is often frightening how difficult it is to visualize fractures even when they are prominent and already known about on CT.

Treatment and prognosis

Skull fractures, if closed and undisplaced, rarely need any direct management, with treatment being aimed at any associated injury (e.g. extradural hematoma). In contrast, depressed fractures will often require surgical intervention for cosmesis and reduction in the incidence of post-traumatic epilepsy . Open (compound) fracture will usually require debridement to reduce the risk of subsequent infection .

Siehe auch:

- epidurales Hämatom

- akzessorische Suturen des Schädels

- kindliche Schädelfraktur

- wachsende Schädelfraktur

- Fraktur Stirnhöhle

- imprimierte Schädelfraktur

- Fissur des Schädels

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Schädelfraktur:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Schädelfraktur: