pelvic fractures

Pelvic fractures can be simple or complex and can involve any part of the bony pelvis. Pelvic fractures can be fatal due to pelvic hemorrhage, and an unstable pelvis requires immediate management.

Epidemiology

Pelvic fractures can be seen in any group of patients. Like much trauma, there is a bimodal distribution with younger male patients involved in high-energy trauma and older female patients presenting after minor trauma.

Clinical presentation

Patients tend to present following trauma with pelvic/hip pain. They will often be immobilized by ambulance crews on arrival and potentially have other life-threatening conditions associated with high-energy trauma.

Pathology

Etiology

Most pelvic fractures result from trauma :

- motor vehicle collision (~50%)

- pedestrian vs motor vehicle (~30%)

- fall from height (~10%)

- motorbike collisions (~4%)

- other e.g. sports injury, low-energy fall

Pelvic insufficiency fractures are common in the elderly.

The type of fracture that occurs as a result of the type of injury (impact or compression), the energy involved and the strength of the bones.

The potential morbidity associated with these fractures is related to the involvement of the pelvic ring. Injuries that result in disruption of the pelvic rings result in a significantly worse prognosis.

Direct impact low-to-moderate energy injuries usually result in a solitary and localized fracture. Compression injuries tend to cause fractures that involve the pelvic ring and are unstable.

Classification

Four main forces have been described in high-energy blunt force trauma that results in unstable pelvic fractures as described in the Young and Burgess classification :

- anteroposterior compression: result in an open book or sprung pelvis fractures

- lateral compression: result in a windswept pelvis

- vertical shear: results in Malgaigne fracture or bucket handle fracture

- combined mechanical: occur when two different force vectors are involved and result in a complex fracture pattern

The Tile classification of pelvic fractures is based on stability rather than mechanism and is considered the precursor of the Young and Burgess system.

Isolated stable pelvic fractures can also occur in the context of lower energy mechanisms or sporting injuries:

- acetabular fracture

- pubic ramus fracture

- iliac wing fracture (Duverney fracture)

- avulsion fractures (e.g. ASIS, iliac crest, ischial tuberosity)

Associated injuries

Pelvic hemorrhage

Pelvic fractures carry a significant risk of uncontrolled pelvic bleeding and exsanguination from pelvic fractures is a real possibility. This may result in pelvic, thigh and/or retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Pelvic angio-embolization should be considered in patients with evidence of persistent blood loss with no evidence of intra-abdominal bleeding prior to surgical fixation .

Higher grade injury patterns that cause major pelvic ligamentous disruption have greater association with vascular injuries due to the close proximity of the pelvic vessels to major ligaments and the pelvic bones .

Pelvic bleeding can be from injured arteries, veins or from the fractured bone itself. Most bleeding (80%) occurs at low pressure due to venous injury or blood oozing from fractured bones. High pressure bleeding (20%) is from arterial injury .

Other complications

Radiographic features

The radiographic features are varied and even for serious and severe injuries can be subtle on plain radiographs.

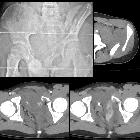

Plain radiograph

X-rays are a quick and simple test that will detect the majority of pelvic fractures. They can be difficult to assess because of the complexity of the shape of the sacrum, pelvis and proximal femora.

CT

CT is the modality of choice for accurately depicting complex acetabular and pelvic ring fractures. After an initial plain radiograph, a CT is often required to make an accurate assessment of the fracture and often aids in surgical decision making.

CT with arterial and venous phases are highly sensitive for detection of pelvic bleeding, and can often distinguish the causes. Occasionally a delayed phase may be of benefit to allow differentiation between active arterial bleeding and a contained vascular injury, for example, a pseudoaneurysm . Delay phases may also aid in the distinction between bleeding and fractured bone fragments. Spectral CT with virtual non-contrast (VNC) reconstructions also allows differentiation of these two entities.

Signs of arterial injury include :

- abrupt narrowing or contouring of an artery (representing intimal injury, thrombosis, vasospasm, or intramural hemorrhage)

- intraluminal linear filling defects (representing dissection)

- focal outpouching (representing pseudoaneurysm)

- active contrast extravasation (representing transmural injury or transection)

- arterial cutoff or non-visablity (representing thrombosis or transection)

- early opacification of veins in the arterial phase (representing arteriovenous fistula)

The most commonly injured arteries are the:

- internal iliac artery

- superior gluteal artery (in pelvic sidewall fractures and fractures involving the greater sciatic foramen)

- obturator artery (in pelvic sidewall fractures)

- internal pudendal artery (in pelvic sidewall and inferior pubic rami fractures)

The most common veins injured are the veins of the presacral plexus and the prevesical veins.

CT cystography is used to detect bladder injury in patients with hematuria or suggestion of bladder rupture, such as free peritoneal fluid of water density .

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment and prognosis depend on the type of injury.

Initial stabilization of pelvic fractures by first responders at the scene, and later by staff in emergency departments, with pelvic binders and sheets have been shown to improve outcomes .

Simple pubic rami fractures are treated by immobilization. Multipart acetabular fractures require reconstruction by an experienced operator. Complex pelvic ring fractures may require external fixation. In these patients, their prognosis is partly dependent on their comorbidities and other related injuries.

Pelvic fractures carry significant mortality and morbidity. It has been reported that ~75% of pre-hospital deaths from motor vehicle collisions are secondary to pelvic fractures .

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Beckenfraktur:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Beckenfraktur: