endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common, chronic gynecological condition defined as the presence of functional endometrial glands and stroma-like lesions outside the uterus. It manifests in three ways; superficial (peritoneal) disease, ovarian disease (endometriomas), and deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is the most complex and surgically challenging form.

Endometriosis has a high association with, although is distinct from adenomyosis (in which endometrial tissue is confined to the uterine musculature). Size is highly variable, ranging from microscopic endometriotic implants to large cysts (endometriomas) and nodules.

Epidemiology

Typically endometriosis presents in young women, with a mean age of diagnosis of 25-29 years , although it is not uncommon among adolescents. Up to 5% of cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Potential risk factors include family history and short menstrual cycles. Racial predisposition remains controversial .

It is difficult to ascertain the overall prevalence of endometriosis, but in women who underwent laparoscopy for various reasons, the prevalence was as follows :

- asymptomatic women (laparoscopy for tubal ligation): 1-7%

- primary infertility: 17-50%

- pelvic pain: 5-21%

Clinical presentation

Symptoms

- infertility

- endometriosis is present in 30-50% of women presenting with infertility

- pelvic pain

- including dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain

- NB: pain is not always cyclic

- including dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain

- unusual symptoms

- gastrointestinal involvement: catamenial diarrhea, rectal bleeding and constipation

- small bowel obstruction can occur from 7 to 23% of patients with intestinal involvement

- vesical involvement: urgency, frequency, hematuria

- thoracic involvement: pleuritic chest pain, pneumothorax, pleural effusions or cyclic hemoptysis

- gastrointestinal involvement: catamenial diarrhea, rectal bleeding and constipation

- asymptomatic

- especially if the disease is isolated to the peritoneum

- stage of disease does not necessarily correlate with the severity of the symptoms

Examination findings

- non-specific

- tenderness along the adnexa and uterosacral ligaments, cul-de-sac +/- thickening or nodularity

- rectovaginal or adnexal masses

Pathology

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains unclear and is subject to much debate; potential mechanisms include:

- metastatic theory: transplantation of endometrial cells (via retrograde menstruation, lymphatic or vascular dissemination, iatrogenic implantation) with probable immune/hormonal/inflammatory mediators ; supporting this theory is that up to 90% of women have bloody peritoneal fluid during the perimenstrual period

- metaplastic theory: retroperitoneal deep endometriosis may originate from metaplasia of Müllerian remnants located in the rectovaginal septum

- induction theory: whereby shed endometrium releases substances that induce undifferentiated mesenchyme to form endometriotic tissue

See the illustration of theories of endometriosis.

Macroscopic

Macroscopic appearances vary depending on the duration of disease and depth of penetration:

- superficial

- superficial endometriosis: Sampson syndrome

- nodules or plaques of varying size from a few millimeters to 2 cm in diameter

- the amount of pigment appears to increase with the age of the lesion: initially, they appear as white plaques, non-pigmented clear vesicles, or red petechiae or flame-like areas; as they age, the color changes to bluish/brownish lesions - these are referred to as “powder burns”, representing hemolyzed blood encased in fibrotic tissue

- additionally, appearance not only varies with age but also with the phase of the menstrual cycle

- deep: penetrating into the retroperitoneal space or the wall of the pelvic organs to a depth of at least 5 mm, and comprises nodules, cysts and secondary scarring

- endometriotic cysts (a.k.a. endometriomas or "chocolate cysts")

- most commonly occur in the ovaries and are the result of repeated cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant

- often there is a complete replacement of ovarian tissue

- cyst walls may become thick and fibrotic with dense adhesions, with a lining that varies in contour (smooth to shaggy) and color (pale-to-brown)

- adhesions and fibrosis can distort normal pelvic anatomy and lead to the obliteration of the pouch of Douglas

Location

The most common location for endometriotic deposits is in the ovaries, and next commonest is in the pelvic peritoneum. Less common locations include C-section scars (scar endometriosis), deep subperitoneal tissues, gastrointestinal tract, bladder, chest, and subcutaneous tissues. The pouch of Douglas, uterosacral ligament and torus uterinus are the most common pelvic sites of involvement .

Deep pelvic endometriosis is divided into:

- anterior cul-de-sac

- posterior cul-de-sac

- retroperitoneal lesions and dependent intraperitoneal locations that may result in infiltrating lesions

- adhesions between the anterior rectal wall and posterior vaginal fornix

- rectovaginal septal involvement

- pelvic sidewall

- including ureteral lesions said to arise from the extension of pelvic foci and ovarian endometriosis

- gastrointestinal tract

- implantation occurs in 12-37% of patients

- rarely proximal to the terminal ileum

- rectosigmoid > appendix > cecum > distal ileum

- urinary tract

- involvement is typically asymptomatic except with severe pelvic disease

- bladder > distal ureter

Extra-abdominal locations include:

- chest

- uncommon

- almost exclusively right-sided

- usually in the setting of long-standing (>5 years) pelvic endometriosis

- cutaneous disease

- scars (scar endometriosis)

- abdominal wall and recesses (e.g. inguinal hernias)

- cervix: associated with cone biopsy

- labia/vulva (via the round ligament)

- canal of Nuck

- inguinal region (inguinal endometriosis)

Radiographic features

Although laparoscopy continues to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis, both ultrasound and MRI are increasingly being used, especially to evaluate deep disease. MRI has high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (91%) . Ultrasound has been shown to have sensitivities and specificity above 90% for deep endometriosis, dependent on location .

Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound has classically been described as a very limited technique for assessing endometriosis beyond the detection of ovarian endometriomas. However, recent literature shows that in expert hands it can present a similar sensitivity to MRI in the detection of intestinal endometriosis . Endometriotic implants with intestinal affectation present an extraluminal growth from the serosa to the innermost layers, with preservation of the layered structure of the intestinal wall. These findings allow to differentiate them from an intestinal neoplasia, since the latter presents a growth from the mucosal layer towards the most external layers and associates loss of the layered structure of the intestinal wall. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can also be helpful in the assessment of these findings . Moreover, given that it can be a cause of small bowel obstruction and considering that this pathology affects young patients, intestinal ultrasound is a validated and useful technique for its detection, avoiding the need for TC studies.

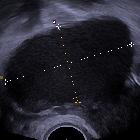

Transvaginal ultrasound can be performed unless declined by the patient. Whilst not able to reliably detect superficial disease, transvaginal ultrasound has been shown to have sensitivity over 90% in detecting deep infiltrating endometriosis as long as the transvaginal ultrasound is extended beyond the uterus and ovaries to include an assessment of the anterior and posterior compartments.

If deep infiltrating endometriosis is found on ultrasound, the scan should be extended to include an assessment of the kidneys to rule out hydronephrosis. In these cases, CEUS can also be helpful to assess if an enhancing lesion in the ureter has an intraluminal (as seen in urothelial neoplasms) or an extraluminal origin (as seen in endometriotic implants) .

Transvaginal ultrasound has the ability to dynamically assess mobility and site-specific tenderness, known as 'soft markers' for endometriosis which are suggestive of superficial disease and pelvic adhesions . The loss of the sliding sign on transvaginal ultrasound assessment indicates obliteration of the pouch of Douglas ,which is an essential piece of information to obtain for surgical planning.

Nodules of endometriosis tend to appear sonographically as solid, hypoechoic, irregular masses. They may contain echogenic foci or small cystic spaces and often show little or no blood flow on color Doppler.

In 2016, the consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group was published, which clearly and systematically outlines the features of deep infiltrating endometriosis by ultrasound:

- uterus: anteverted-retroflexed uterus ('question mark sign') is often seen with severe posterior compartment deep infiltrating endometriosis

- ovarian endometriomas

- typically unilocular cystic lesions containing uniform low-level echoes (ground glass appearance)

- no blood flow on color Doppler (color score 1)

- maybe single or multiple

- can have an atypical appearance including multiple locations and papillary projection

- endometriomas may undergo decidualization in pregnancy, in which case they can be confused with an ovarian malignancy

- ‘kissing’ ovaries sign describes ovaries which are adherent to one another posterior to the uterus and is frequently seen with bilateral endometriomas.

- fallopian tubes: hydrosalpinx may be due to endometriosis

- urinary bladder

- bladder deep infiltrating endometriosis occurs more frequently in the bladder base and bladder dome than in the extra‐abdominal bladder

- the appearance of nodules can be varied, including hypoechoic linear or spherical lesions, with or without regular contours involving the muscularis (most common) or (sub)mucosa of the bladder

- ureters: may appear dilated with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Dilatation of the ureter due to endometriosis is caused by stricture (from either extrinsic compression or intrinsic infiltration)

- ureterovesical region

- can be obliterated due to adhesions. Should be assessed with the sliding sign (like the pouch of Douglas)

- up to 1/3 of women with a previous cesarean section will have adhesions in this region

- rectovaginal septum

- deep infiltrating endometriosis nodule seen on transvaginal ultrasound in the rectovaginal space below the line passing along the lower border of the posterior lip of the cervix

- deep infiltrating endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum is very rare

- posterior vaginal wall/ posterior vaginal fornix

- thickening of the vaginal wall

- a discrete hypoechoic nodule in the vaginal wall which may be homogeneous or inhomogeneous, with or without large cystic areas and there may or may not be cystic areas surrounding the nodule

- uterosacral ligaments

- hypoechoic nodule with regular or irregular margins is seen within the peritoneal fat surrounding the uterosacral ligament. The lesion may be isolated or may be part of a larger nodule extending into the vagina or into other surrounding structures

- thickening of the white line of the uterosacral ligaments (>5.8mm) has been shown to have a strong association with endometriosis on or near the uterosacral ligaments

- rectosigmoid colon

- nodules can be single or multifocal. A second or subsequent rectal lesions has been demonstrated to occur in 54.6% of cases

- bowel nodules are hypoechoic and in some cases a thinner section or a ‘tail’ is noted at one end, resembling a ‘comet’

- retraction and adhesion possible, resulting in the so‐called ‘Indian headdress’ or ‘moose antler’ sign

- lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters.

- pouch of Douglas

- the pouch of Douglas is considered obliterated if the sliding sign is negative (ie. if the rectum and uterus do not slide apart)

- obliteration can be partial or complete

Despite repeated hemorrhage, findings of acute hemorrhage are uncommon in endometriomas (<10%), such as layering blood products or a retractile thrombus . Unlike many other ovarian cysts, endometriomas do not typically resolve.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS)

Endometriotic implants present a variable contrast enhancement and can appear as lesions with homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement with a non-enhanced center, depending on the associated fibrotic component. It is important to remember that ultrasound contrast agent (sulphur hexafluorid microbubbles, Sonovue) is purely intravascular (unlike iodine or gadolinium-based contrasts, which have an interstitial phase), so an enhancing lesion in the CEUS reflects a vascularized lesion. Thus, the fibrotic areas will not present contrast enhancement.

The use of CEUS in deep pelvic endometriosis can be useful to assess the preservation of the layered structure of the intestinal wall (differentiating it from intestinal neoplasia) to define the extension and morphology of the implant, and to assess an extrinsic origin in cases of ureteral lesion (differentiating it from urothelial neoplasia).

MRI

Technique: pelvic MRI protocol - endometriosis.

MRI has greater specificity for the diagnosis of endometriomas than the other non-invasive imaging techniques and thus has a role to play in the evaluation of adnexal masses, as well as assessing for the response to medical therapy (see below) potentially eliminating the need for follow-up laparoscopy. Typically the lesions that can be detected with MRI are those that contain blood products .

- hemorrhagic “powder burn”

- lesions appear bright on T1 fat-saturated sequences

- small solid deep lesions

- may be hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2

- adhesions and fibrosis

- isointense to pelvic muscle on both T1 and T2 weighted images

- spiculated low signal intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces

- distortion of normal anatomy

- posterior displacement of the uterus

- kissing ovaries sign: seen in the severe forms of the disease

- angulation of bowel loops

- elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix

- loculated fluid collections

- hydrosalpinx

- endometriomas

- <5 mm: early-stage disease; >15 mm: advanced disease

- shading sign : may be less likely to respond to medical treatment

- low T1 and T2 due to tissue and hemosiderin-laden macrophages

- diagnostic criteria:

- multiple cysts with T1 hyperintensity OR

- one or more cysts with high T1 and shading on T2

- uterosacral involvement

- normal uterosacral ligaments are smooth and of regular contour

- irregular margins

- asymmetry

- nodularity and thickening medially (>9 mm)

- altered T2 signal: isointense (50%), hypointense (40%) or hyperintense (10%) compared to myometrium

- if bilateral uterosacral involvement with additional involvement, torus uterinus involvement results in an arciform abnormality

- vaginal involvement

- loss of hypointense signal of the posterior vaginal wall on T2

- thickening, nodules and/or masses also potentially seen

- pouch of Douglas

- partial to complete obliteration

- suspended or lateralized fluid collections

- rectovaginal septum: nodules or masses that have passed through the lower border of the posterior lip of the cervix

- gastrointestinal tract

- MRI has a low sensitivity (33%) for detecting rectal lesions due to artifacts related to rectal content; sensitivity may be increased with the use of water enema, endovaginal coils and phased array coils

- rectal wall thickening

- anterior displacement of the rectum

- abnormal angulation

- loss of fat plane between uterus and bowel

- inflammatory response due to repeated hemorrhage can lead to adhesions, strictures and bowel obstructions

- MRI has a low sensitivity (33%) for detecting rectal lesions due to artifacts related to rectal content; sensitivity may be increased with the use of water enema, endovaginal coils and phased array coils

- urinary tract

- bladder

- localized or diffuse bladder wall thickening

- signal intensity abnormality

- nodules or masses usually located at the level of the vesicouterine pouch

- involvement of bladder mucosa is rare

- bladder

- chest

- catamenial pneumothorax

- hemothorax

- lung nodules

- cutaneous tissues: nodules

- malignant transformation: solid enhancing components

Limitations of MRI

Despite all the advantages of MRI over all other imaging modalities, it nonetheless has a number of limitations, including:

- non-pigmented lesions will not be hyperintense on T1, and thus harder to detect

- small foci may have variable signal intensity

- may appear similar to normal endometrium: low T1, high T2

- hypointense on all sequences

- hyperintense on all sequences

- plaque-like implants are difficult to delineate

- adhesions cannot be directly identified, usually relying on the distortion of normal anatomy to imply their existence

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment of endometriosis can be “expectant”, medical or surgical.

Medical treatment

Targets hormonal regulation, and includes medication with:

- danazol (a synthetic androgen): suppresses estrogen production

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GRH) analogs: control the menstrual cycle

- oral contraceptive pill: suppresses cyclical hemorrhage

Surgery

- laparoscopic (conservative surgery)

- adhesiolysis

- partial cystectomy for resection of anterior cul-de-sac involvement provided ureteric reimplantation does not need to be performed

- uterosacral ligament excision

- used in combination with the vaginal approach for vaginal disease

- laparotomy

- hysterectomy and oophorectomy

- bowel involvement

Complications

Malignant transformation of an endometrioma has been documented, but is rare, occurring in <1% of cases. It is usually in the form of endometrioid carcinoma, or less commonly clear cell carcinoma. Thus, annual ultrasound examinations of endometriomas have been advocated by some.

Differential diagnosis

Differential considerations on MRI for endometriomas include:

- dermoid cysts

- endometriomas have homogeneous high signal intensity on T1 which does not suppress on T1FS, unlike a dermoid which shows signal drop out on fat suppression images and chemical shift artifact

- hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: endometriomas rarely present with acute symptoms and do not resolve over time

- mucinous lesions: e.g. ovarian mucinous tumors

- increased signal on T1 but less intense than fat or blood

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Endometriose:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Endometriose: