staghorn calculus

Staghorn calculi, also sometimes called coral calculi, are renal calculi that obtain their characteristic shape by forming a cast of the renal pelvis and calyces, thus resembling the horns of a stag. They refers to struvite calculus involving the renal pelvis and extending into atleast two calyces.

For a general discussion of renal calculi please refer to nephrolithiasis.

Epidemiology

Staghorn calculi are the result of recurrent infection and are thus more commonly encountered inwomen , those with renal tract anomalies, reflux, spinal cord injuries, neurogenic bladder or ileal ureteral diversion.

Clinical presentation

The majority of staghorn calculi are symptomatic, presenting with fever, hematuria, flank pain and potentially septicemia and abscess formation.

Pathology

Staghorn calculi are composed of struvite (chemically this is magnesium ammonium phosphate or MAP) and are usually seen in the setting of recurrent urinary tract infection with urease-producing bacteria (e.g. Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and Enterobacter). Urease hydrolyzes urea to ammonium with an increase in the urinary pH .

Struvite accounts for approximately 70% of the composition of these calculi and is usually mixed with calcium phosphate thus rendering them radiopaque on both plain films and CT. Uric acid and cystine are the underlying components of a minority of these calculi .

Radiographic features

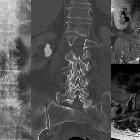

Plain radiograph

The vast majority of staghorn calculi are radiopaque and appear as branching calcific densities overlying the renal outline and may mimic an excretory phase intravenous pyelogram. Lamination within the stone is common.

Ultrasound

The collecting system is filled with a densely calcified mass, producing marked posterior acoustic shadowing.

CT

Staghorn calculi are radiopaque and conform to the renal pelvis and calyces, which are often to some degree dilated. When viewed on bone windows they have a laminated appearance, due to alternating bands of magnesium ammonium phosphate and calcium phosphate .

Treatment and prognosis

Staghorn calculi need to be treated surgically, usually PCNL (percutaneous nephrolithotomy) +/- ESWL (extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy) and the entire stone removed, including small fragments, as otherwise, these residual fragments act as a reservoir for infection and recurrent stone formation.

If left untreated, staghorn calculi result in chronic infection and eventually may progress to xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis .

Differential diagnosis

There is usually little differential, provided intravenous contrast has not been administered. In the latter situation, the opaque collecting system may be attributed to contrast rather than the calculus, especially when staghorn calculi are bilateral.

Siehe auch:

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Nierenausgussstein:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Nierenausgussstein: