TCC of the renal pelvis

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the renal pelvis, also called urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC) of the renal pelvis, is uncommon compared to renal cell carcinoma and can be challenging to identify on routine imaging when small.

This article concerns itself with transitional cell carcinomas of the renal pelvis specifically. Related articles include:

- general discussion: transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract

- transitional cell carcinomas in other locations:

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of transitional cell carcinomas of the renal pelvis is similar to those of the rest of the urinary tract: please refer to TCCs of urinary tract for further details.

TCCs of the renal pelvis are 50x less common than bladder TCCs but 2-3x more common than those of the ureter, representing differences in surface area, and likely also stasis (and thus exposure of urothelium to carcinogens in urine) . They are significantly less common than renal cell carcinomas and constitute only approximately 5-10% of renal tumors .

As is the case with transitional cell carcinomas elsewhere, renal pelvis tumors are more common in males and are typically diagnosed between 60-70 years of age .

Associations

- hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC): Lynch type II

- horseshoe kidney

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation is most frequently with microscopic or macroscopic hematuria. If the tumor is located at the pelviureteric junction, then symptomatic hydronephrosis may be the presenting symptom (flank pain) and clot-related renal colic may mimic renal calculi.

Some patients only present once metastatic disease becomes symptomatic, with constitutional symptoms (e.g. weight loss) or focal symptoms due to a metastatic deposit (e.g. pathological fracture).

Urine cytology is insensitive in tumors confined to the renal pelvis, being positive in only 14% of patients .

Pathology

Transitional cell carcinomas account for 85% of all uroepithelial tumors of the renal pelvis, the remaining 5% is made up of squamous cell carcinoma (the majority) and adenocarcinoma (rare) . They have one of two main morphologic patterns:

- account for >85% tumors

- multiple frond-like papillary projections

- tend to be low grade and invasion beyond the mucosa is a late feature

- sessile or nodular tumors

- tend to be high grade with early invasion beyond the mucosa

Tumors are divided into three histological grades. However, note should be made that stage is far more prognostically important than tumor grade :

- grade I: well differentiated

- grade II: moderately differentiated

- grade III: poorly/undifferentiated

Radiographic features

Radiographic appearances depend on the morphology: papillary tumors appear as soft tissue density filling defects whereas non-papillary/infiltrating tumors are harder to detect as they are often sessile.

Plain radiograph

Plain radiograph has little role to play in the diagnosis or assessment of transitional cell carcinomas. Rarely a large mass may be seen; even in such cases, findings are non-specific. Tumoral calcification is rare, seen in only 2-7% .

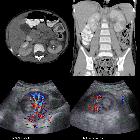

Ultrasound

On ultrasound examination, transitional cell carcinomas appear as solid, albeit hypoechoic masses located within the renal pelvis or a dilated calyx (also known as an oncocalyx). In patients in whom ultrasound is technically difficult care must be taken to not interpret the hypoechoic mass as hydronephrosis.

Rarely, transitional cell carcinomas with squamous metaplasia and abundant keratin formation appear echogenic and densely shadowing and may mimic a renal calculus .

CT

Transitional cell carcinomas are typically of soft tissue density (8-30HU) with only mild enhancement (18-55HU), usually significantly less enhancing than renal parenchyma or renal cell carcinomas (although the distinction cannot always be made). They are usually centered on the renal pelvis (rather than the renal parenchyma as is the case with RCC) and range in size from small filling defects (difficult to see without distension or collecting system contrast) to large masses which obliterate the renal sinus fat (TCC is one of the causes of the so-called faceless kidney) .

Unlike renal cell carcinomas that tend to distort the renal outline, even large infiltrating transitional cell carcinomas maintain a normal renal shape . Larger tumors may have areas of necrosis .

In cases of the tumor being small and located at the pelviureteric junction with resultant hydronephrosis, a small soft tissue mass should be sought. In contrast to congenital PUJ obstruction, the calyces are typically dilated, and the renal pelvis wall may be thickened .

Occasionally numerous small calcification may be present, located on the surface of papillary projections .

CT or conventional urography and direct pyelography

The collecting system can be opacified by contrast media in a number of ways:

CT urography (CT IVP) has largely replaced conventional plain film urography and is the mainstay of both diagnosis and staging (see staging of TTCs of the renal pelvis) with sensitivity (96%) and specificity (99%) .

All imaging modalities which outline the collecting system with contrast rely on the same possible findings:

Also, an obstructive lesion may lead to hydronephrosis and/or non-functioning kidney (not necessarily with hydronephrosis).

When tumors are large and of papillary morphology, contrast filling the interstices between papillary projections can lead to a dappled appearance referred to as the stipple sign . This if more commonly seen in the bladder when tumors have room to grow to larger dimensions.

A calyx may be distended by a tumor within it (known as an oncocalyx) or prevented from filling with contrast (known as a phantom calyx) .

Angiography (DSA)

Angiography is usually not performed. If obtained, however, transitional cell carcinomas tend to be hypovascular, and invasion of the renal vein, although reported, is uncommon compared to renal cell carcinomas .

MRI

At this stage, there is little role for MR urography outside of research and in selected patients with adverse reactions to iodinated contrast medium.

Transitional cell carcinomas are isointense to renal parenchyma on both T1 and T2 weighted images . Following administration of gadolinium, transitional cell carcinomas enhance but less so than normal renal parenchyma .

Treatment and prognosis

Typically, and certainly, in the case of locally advanced tumors, treatment is surgical consisting of a nephroureterectomy, taking not only the kidney but also the ureter and a cuff of the bladder at the vesicoureteric junction .

In low stage tumors and especially in patients with bilateral tumors (e.g. Balkan nephropathy) or solitary kidneys, renal-sparing surgery may be attempted, in which tumors are locally excised often endoscopically (percutaneous or transurethral approach) .

Instillation of bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) or mitomycin C into the upper tract has been investigated as an alternative to surgery in some cases .

Prognosis depends on the stage of the tumor (see staging of TTCs of the renal pelvis) and histological grade has little influence .

As the majority of renal pelvis transitional cell carcinomas are low grade, the prognosis is typically good, with a 5-year survival of over 90% .

A critical part of the management of patients with transitional cell carcinomas is an awareness of the high rate of recurrence due to field effect on the urothelium. Approximately 40% of patients with an upper urinary tract TCC will go on to develop one or more TCCs of the bladder .

Metastases are most frequently to liver, bone, and lung .

Differential diagnosis

The differential depends on the radiographic appearance:

- filling defect within renal pelvis/dilated calyx

- renal stone

- usually significantly higher attenuating

- non-enhancing

- blood clot

- may be similar in attenuation (blood clot is usually a little higher)

- does not enhance

- changes configuration on short-term follow-up

- pyelitis cystica

- renal tuberculosis

- papillary necrosis

- renal stone

- distortion or obliteration of calyces by renal mass

- renal cell carcinoma

- often more vascular and thus more enhancing

- tends to distort the renal outline

- kidney metastasis

- renal medullary carcinoma

- renal lymphoma

- renal abscess

- focal xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis

- renal tuberculosis

- renal cell carcinoma

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu UCC of the renal pelvis:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu UCC of the renal pelvis: