Blasenstein

Bladder calculi occur either from migrated renal calculi or urinary stasis. Bladder calculi can be divided into primary and secondary stones:

- Primary: stones formed in sterile urine, usually renal calculi which have migrated down into the bladder

- Secondary: stones form de novo in the bladder or from concretions on foreign material (e.g. urinary catheters)

Epidemiology

Secondary bladder calculi, in otherwise normal bladders, were previously common, but are now very uncommon in Western nations . When encountered, the most common cause is due to urinary stasis, including from:

Family history is found in up to one-third of idiopathic cases .

Clinical presentation

Bladder calculi may present with pain, infection, hematuria or may be asymptomatic.

Radiographic features

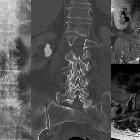

Plain radiograph

Usually densely radiopaque, calculi may be single or multiple and are often large. Frequently lamination is observed internally, like the skin of an onion.

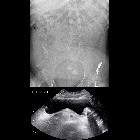

Ultrasound

Sonographically they are mobile, echogenic, and shadow distally. They may be associated with bladder wall thickening due to inflammation.

Treatment and prognosis

The earliest method of operative removal of bladder calculus was performed via the perineal route with the patient in a supine position and the legs elevated, hence the term lithotomy position.

Differential diagnosis

- occasionally a calculus which appears to be in the bladder is actually in the most distal part of the ureterovesical junction: rescanning the patient in the prone position can help to distinguish these from true bladder calculi

- for a tiny calculus abutting the anterior margin of the bladder, consider a calcification at the insertion of a urachal remnant into the urinary bladder

- for other pelvic calcifications which could just outside the course of the bladder, consider entities such as vascular calcification, most commonly phleboliths

Siehe auch:

- Urolithiasis

- Verkalkungen der Blase

- Fremdkörper

- Nierensteine

- Leiomyofibrom Uterus

- Harnblase

- neurogene Blase

- Blasenentleerungsstörung

- bladder calcification (mnemonic)

- verkalkter Tumor der Blase

- Blasenstein in Blasendivertikel

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Blasenstein:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Blasenstein: