Pericardial constriction

Constrictive pericarditis (or perhaps better termed pericardial constriction) is a type of pericarditis which leads to diastolic dysfunction and potential symptoms of right heart failure.

Epidemiology

No single demographic is affected as there are numerous causes of constrictive pericarditis.

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation is dominated by restricted diastolic ventricular filling resulting in an increase in diastolic pressure in all four cardiac chambers. Patients typically present with symptoms of both left and right-sided heart failure including:

- dyspnea

- orthopnea

- easy fatigability

- hepatomegaly

- ascites

Pathology

Characterized by fibrous or calcific constrictive thickening of the pericardium, which prevents normal diastolic filling of the heart. It may follow any type of pericardial effusion and may develop within a variable time frame ranging from two or three months to a number of years.

Etiology

- idiopathic (most common)

- pericardial injury

- previous cardiac surgery (second most common)

- radiotherapy (third most common)

- post-myocardial infarction (Dressler syndrome)

- infection

- tuberculosis (previously common)

- viral infection

- pyogenic infection

- sarcoidosis

- metabolic disorder: uremia

- connective-tissue diseases

- rheumatic fever (rare)

- systemic lupus erythematosus (rare)

- scleroderma

- malignancy: mesothelioma, lymphoma, leukemia and cancer lung or breast

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

In approximately 50% of cases, there is visible pericardial calcification on chest radiographs.

Echocardiography

Although a thickened pericardium is often present, transthoracic insonation rarely allows satisfactory visualization; the presence of a pleural or pericardial effusion may provide an adequate window, although the latter may further obscure landmarks if sufficiently exudative.

Conversely, a thin and smooth but highly non-compliant pericardium may also be present. The hemodynamic consequences of constriction occur due to the pericardium insulating the cardiac chambers from changes in intra-thoracic pressure, although lesser degrees of constriction may occur.

Exaggerated ventricular interdependence and intrathoracic-intracardiac dissociation. The pathognomonic finding is respirophasic septal shifting with a characteristic "shudder" due to alternate rapid early filling of the ventricles

B-mode

- plethoric inferior vena cava with absent respirophasic variation

- abrupt, eccentric inflection with flattening of left ventricular lateral wall in early diastole

- represents tethering to adherent pericardium

- may result in lateral mitral annulus e' to appear disproportionately low when compared to septal e'

- phenomenon referred to as "annulus reversus"

- abnormal septal motion

- characteristic finding is exaggerated respirophasic septal shifts

- characteristic "shudder" due to the alternate rapid early filling of the ventricles

- characteristic finding is exaggerated respirophasic septal shifts

Spectral Doppler

- mitral valve inflow demonstrates an inappropriately elevated E/A ratio

- deceleration time <160 ms

- mitral and/or tricuspid valve inflow patterns demonstrate pronounced respiratory variation in E-wave velocity

- >25% variance in peak velocity considered excessive

- tricuspid inflow is augmented during inspiration and reduced during expiration, while the mitral valve demonstrates the opposite

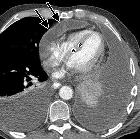

CT

CT is very sensitive in demonstrating calcification of the pericardium which is suggestive of the disease if found in the proper clinical setting. A thickened pericardium (>4 mm) on its own does not indicate constrictive pericarditis . Contrast-enhanced CT may also show signs of cardiac failure like septal flattening and retrograde flow of contrast into the dilated inferior vena cava and hepatic veins.

MRI

The pericardium is often thickened to >4 mm. MRI is better than CT at differentiating between pericardial fluid and thickened pericardium . Cine MRI may also demonstrate septal flattening and septal bounce.

Treatment and prognosis

Constrictive pericarditis is potentially curable by a pericardiectomy.

Differential diagnosis

Clinically, it is difficult to differentiate between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. It is important to distinguish between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy as the former benefit from pericardial stripping.

Siehe auch:

- Perikarditis

- restrictive cardiomyopathy

- Pericarditis calcarea

- kardiale Beteiligung bei Sarkoidose

- primäres Mesotheliom des Perikards

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Pericarditis constrictiva:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Pericarditis constrictiva: