achilles tendon tear

Achilles tendon tears are the most common ankle tendon injuries, and are most commonly seen secondary to sports-related injury, especially squash and basketball.

Epidemiology

There is strong male over-representation presumably as a result of the predominantly sport related etiology. Patients are typically aged 30-50 years and have no antecedent history of calf or heel pain. There are however numerous recognized predisposing factors including:

- intratendinous steroid injection

- diabetes mellitus

- systemic inflammatory illnesses

- repeated microtrauma

- gout

- fluoroquinolone antibiotics

- ochronosis

- hyperparathyroidism

Clinical presentation

Typically patients present with sudden onset of pain and swelling in the Achilles region, often accompanied by an audible snap during forceful dorsiflexion of the foot. A classic example is that of an unfit 'weekend warrior' playing squash.

If complete a defect may be felt and the patient will have only minimal plantar flexion against resistance.

Pathology

The spectrum of tears ranges from microtears to interstitial tears (parallel to the long axis of the Achilles), to partial tears, and eventually to complete tears.

Tears can be acute or chronic, with repeated minor trauma. At the mildest end of the spectrum all that may be present is peritendonitis.

Location

Typically, in a young 'normal' individual, the Achilles tendon ruptures in the 'critical zone', which is a region of relative watershed hypovascularity 2-6 cm proximal to insertion.

Classification

The Achilles tendon tear classification is primarily based on the degree of retraction.

Radiographic features

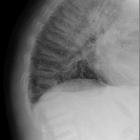

Plain radiograph

Plain radiographs may show soft tissue swelling and obliteration of pre-Achilles fat pad (Kager's triangle).

Ultrasound

For partial thickness tears

- there is often enlargement of the tendon ( >1 cm) with abnormally hypoechoic or anechoic areas within which correspond to the tear and associated adjacent tendinosis

For full thickness tears

- often shows separation of the torn ends with a contour change of the tendon

- there is acoustic shadowing at the margins of the tear from sound beam refraction, and adjacent hypoechoic tendinosis

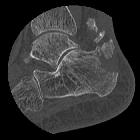

MRI

Appearances can vary:

- a full-thickness tear often shows a tendinous gap filled with edema or blood

- complete rupture shows retraction of tendon ends

- T2: partial thickness or interstitial tears may show high signal on long TR, and tendon swelling to >7 mm AP

When a plantaris muscle is present then its tendon is usually spared due to its more anterior insertion on the calcaneum.

Post-operative

- post-operative MR imaging may show a tendon gap although this tends to resolve in around 12 weeks

- post-operatively, Achilles tendon may appear thicker on MR follow up

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment depends on the extent of the tear. Partial thickness tears can initially be treated conservatively, with surgery reserved for failure of conservative management, on in some cases for high-performance athletes. Full-thickness tears are normally surgically repaired. If the patient is not deemed suitable for surgical repair (frail, ill, etc.) casting of the ankle in the talipes equinus position may be an alternative.

Surgical repair results in a shorter Achilles tendon and better greater calf muscle strength (less soleus atrophy) than non-surgical treatment .

History and etymology

A true rupture of the Achilles tendon was first described by Ambroise Pare in 1575 and first reported in the medical literature in 1633 .

See also

- Haglund syndrome

- calcaneal tuberosity avulsion fracture is a separate entity.

- ossification of the Achilles tendon

Siehe auch:

- Rheumatoide Arthritis

- Gicht

- primärer Hyperparathyreoidismus

- systemischer Lupus Erythematodes

- Musculus plantaris

- calcaneal tuberosity avulsion fracture

- Ochronose

- Verknöcherungen der Achillessehne

- Kager's triangle

- Bursitis subachilleae

- Haglund-Exostose

- Ruptur Musculus plantaris

- achilles tendon tear classification

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Achillessehnenruptur:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Achillessehnenruptur: