adrenal adenoma

Adrenal adenomas, also known as adenomata, are the most common adrenal lesion and are often found incidentally during abdominal imaging for other reasons. In all cases, but especially in the setting of known current or previous malignancy, adrenal adenomas need to be distinguished from adrenal metastases or other adrenal malignancies.

Terminology

The term incidental adrenal lesion/nodule (also colloquially known as an incidentaloma) is sometimes used interchangeably with adrenal adenoma, although in truth an incidental adrenal lesion includes all pathologies (including malignancies). As such, the term should be avoided lest it results in confusion.

Epidemiology

Adrenal adenomas are found in almost all age groups but increase in frequency with age .

Clinical presentation

The majority (~95%) of adrenal adenomas are non-functioning, in which case they are asymptomatic. If found incidentally, please refer to the Management of incidental adrenal masses: American College of Radiology white paper.

Patients with hyperfunctioning adrenal gland adenomas present with manifestations of excess hormone secretion. The most common disease states caused by functioning adenomas are Cushing syndrome (due to excess cortisol production), Conn syndrome (due to excess aldosterone production), or sex hormone-related symptoms .

Radiographic features

Imaging plays a key role in assessing the vast number of incidental adrenal lesions, the majority of which are adrenal adenomas. Correlation with previous imaging is often useful, as a lesion which has not changed over some years is unlikely to be malignant.

General

Adrenal adenomas can be divided into those with a typical or an atypical appearance.

Typical adenomas are:

- small: <3 cm

- homogeneous and low density

Atypical features include:

- hemorrhage

- calcification

- necrosis

- lack or paucity of fat

- large

- if >4 cm: 70% malignant (excluding adrenal myelolipomas which are easily recognized due to fat, and pheochromocytomas which are usually recognized biochemically)

- if >6 cm: 85% malignant

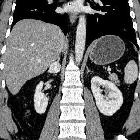

CT

CT is often the modality which identifies an adrenal mass. Fortunately, density evaluation of an adrenal lesion is highly sensitive and specific as 70% of adrenal adenomas contain significant intracellular fat. Lipid-poor adenomas are more difficult to diagnose as the CT density increases and approach that of soft tissue.

For lipid-poor lesions, the contrast washout rate can be calculated using CT. Adenomas typically have rapid contrast washout, whereas non-adenomas tend to wash out more slowly. There are different protocols, and some controversy exists as to which protocol is the best. A 5 or 10-minute protocol may be more suitable for busy CT lists. However, there is evidence that a 15 minutes post-contrast protocol has better diagnostic accuracy .

- non-contrast imaging

- <0 HU: considered 47% sensitive and 100% specific

- <10 HU: considered 71% sensitive and 98% specific

- washout imaging

It is important to note that hypervascular metastases may show identical washout values, particularly those from renal cell carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma . An alternative diagnosis to adrenal adenoma must be considered when there is a value >120 HU on the portal venous phase, particularly in cases with a prior history of neoplasm .

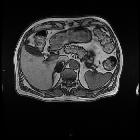

MRI

Chemical shift imaging is the most reliable for diagnosis especially when CT findings are equivocal. Because of the high sensitivity of chemical shift, MR imaging to minute amounts of intravoxel (i.e. intracellular) fat, MR imaging demonstrates signal dropout on opposed-phase images in the majority of adenomas, and a drop in signal intensity of >16.5% is considered diagnostic for an adenoma . Rather than measuring the signal, one can compare the adenoma in and out of phase, with images windowed identically, a visible loss of signal is diagnostic of an adenoma . Do not use the liver as a reference, as it can change in signal between in- and out-of-phase imaging, depending on the presence of hemochromatosis or hepatic steatosis .

As MRIs are usually performed to help define indeterminate adrenal lesions seen on CT, the sensitivity and specificity depend on the CT density. MRI is useful for adrenal masses with an attenuation <30 HU . Signal dropout on out-of-phase imaging for:

- 10-30 HU on CT is 89% sensitive and 100% specific

- 10-20 HU on CT is 100% sensitive and 100% specific

Fat-containing metastases (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma) can demonstrate loss of signal similar to adenomas . Malignant adrenal lesions also demonstrate restricted diffusion .

Treatment and prognosis

Small adrenal masses with manifestations of hormonal excess require resection, as do large (>3-5 cm) non-functioning adrenal mass lesions, as they are considered potentially malignant (see adrenal carcinoma).

A small adrenal lesion with typical features of an adenoma and without biochemical abnormality can be safely left in situ. Some studies demonstrate that up to 40% of adenomas may grow and approximately 10% have been shown to resolve .

In patients with a known malignancy, ~50% of non-specific adrenal nodules will represent adrenal adenomas.

Differential diagnosis

Consider other adrenal lesions such as:

- adrenal cortical carcinoma

- pheochromocytoma

- adrenal metastasis

- focal adrenal granulomatous disease

- adrenal myelolipoma

Practical points

attenuation measurements should have an ROI covering two-thirds of the lesion and excluding calcifications and the periphery of the lesion to avoid volume averaging

small (<3 cm), homogeneous, and low density (<10 HU) are leave-alone lesions

lesions with attenuation values grater than 20-30HU on non-contrast CT are unlikely to be shown as adenomas on chemical shift MRI and may rather benefit from a dynamic contrast CT study

if >120 HU on the portal venous phase, the washout value should be ignored, as the lesion is most likely a hypervascular metastasis or pheochromocytoma rather than a lipid-poor adenoma

be aware that HCC and RCC may contain intracellular fat and, therefore, their metastasis may mimic adenoma

Siehe auch:

- Myelolipom Nebenniere

- Phäochromozytom

- Nebennierenrindenkarzinom

- Nebennierenläsionen

- Inzidentalom

- Conn-Syndrom

und weiter:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Nebennierenadenom:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Nebennierenadenom: