Achalasie

Achalasia (primary achalasia) is a failure of organized esophageal peristalsis causing impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, and resulting in food stasis and often marked dilatation of the esophagus.

Obstruction of the distal esophagus from other non-functional etiologies, notably malignancy, may have a similar presentation and has been termed "secondary achalasia" or "pseudoachalasia".

Epidemiology

Primary achalasia is most frequently seen in middle and late adulthood (age 30 to 70 years) with no gender predilection . Most cases are idiopathic; however, a similar appearance may occur in Chagas disease. Authors differ as to whether to reserve the term achalasia for idiopathic cases or to include Chagas disease. Patients with Allgrove syndrome (triple A syndrome) also have achalasia which is very similar to the primary form of the disease.

Clinical presentation

Patients typically present with:

- dysphagia for both solids and liquids: this is in contradistinction to dysphagia for solids only in cases of esophageal carcinoma

- chest pain/discomfort

- eventual regurgitation (not acidic!)

Symptoms are initially intermittent. Patients may also present with complications of long-standing achalasia:

- esophageal carcinoma

- the most dreaded complication, seen in ~5%, most often in the mid-esophagus

- thought to occur because of chronic irritation of the mucosa by stasis of food and secretions

- aspiration pneumonia: the chronic presence of fluid debris in the esophagus makes patients very prone to aspiration

- candida esophagitis

- acute airway obstruction: this is a rare complication requiring immediate esophageal decompression with a nasogastric tube

Pathology

The lower esophageal sphincter fails to relax, either partially or completely, with elevated pressures demonstrated manometrically . This appears to be due to loss/destruction of neurons in the Auerbach/myenteric plexus. Early in the course of achalasia, the lower esophageal sphincter tone may be normal or changes may be subtle.

Peristalsis in the distal smooth muscle segment of the esophagus is eventually lost due to a combination of damage to the Auerbach plexus and vagus nerve (possibly partly due to damage at the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve).

Classification

It may be divided into three distinct types based on manometric patterns:

- type I (classic) with minimal contractility in the esophageal body

- type II with intermittent periods of pan-esophageal pressurisation

- type III (spastic) with premature or spastic distal esophageal contractions

Radiographic features

Achalasia characteristically involves a short segment (less than 3.5 cm in length) of the distal esophagus.

Plain radiograph

Chest radiograph findings include:

- convex opacity overlapping the right mediastinum. Occasionally may present as a left convex opacity if the thoracic aorta is tortuous.

- air-fluid level due to stasis in a thoracic esophagus filled with retained secretions and food

- small or absent gastric bubble

- anterior displacement and bowing of the trachea on the lateral view

- patchy alveolar opacities, usually bilateral, may be seen. These represent acute pneumonitis or chronic aspiration pneumonia related to dysphagia.

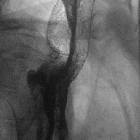

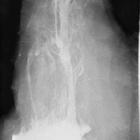

Fluoroscopy with barium swallow

A barium swallow study may be used to confirm esophageal dilatation, in addition to assessing for mucosal abnormalities.

Findings include:

- bird beak sign or rat tail sign

- esophageal dilatation

- tram track appearance: central longitudinal lucency bounded by barium on both sides

- incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation that is not coordinated with esophageal contraction

- pooling or stasis of barium in the esophagus when the esophagus has become atonic or non-contractile (a late feature in the disease)

- uncoordinated, non-propulsive, tertiary contractions (see case 1)

- failure of normal peristalsis to clear the esophagus of barium when the patient is in the recumbent position, with no primary waves identified

- when the barium column is high enough (with the patient standing), the hydrostatic pressure can overcome the lower esophageal sphincter pressure, allowing passage of esophageal content

- a hot or carbonated drink during the exam may help visualize sphincter relaxation and barium emptying

CT

Patients with uncomplicated achalasia demonstrate a dilated, thin-walled esophagus filled with fluid/food debris.

Overall, CT has little role in directly assessing patients with achalasia, but is useful in assessing common complications. Careful assessment of the wall of the esophagus should be undertaken to identify any focal regions of thickening which may indicate malignancy. The lungs should be inspected for evidence of aspiration.

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment is aimed at allowing adequate drainage of the esophagus into the stomach. Options include :

- lifestyle changes

- eating slowly, increasing water intake with meals, avoiding eating near bedtime

- avoiding foods that aggravate gastro-esophageal reflux

- calcium channel blockers

- ineffective in the long term

- may be used while preparing for definitive treatment

- pneumatic dilatation

- effective in up 90% of patients

- 3-5% risk of bleeding/perforation

- botulinum toxin injection

- lasts only ~12 months per treatment

- may scar the submucosa leading to increased risk of perforation during subsequent myotomy

- surgical myotomy (e.g. Heller myotomy)

- effective in up to 96% of patients

- peroral esophageal myotomy (POEM procedure) is a newer minimally-invasive technique which may be used in select patients

- 10-30% of patients develop gastro-esophageal reflux, and thus it is often combined with a fundoplication (e.g. Dor, Toupet, Nissen)

There is a variable response to treatment following endoscopic or surgical myotomy based on which achalasia subtype is present :

- type I intermediate prognosis (81%) inversely associated with the degree of esophageal dilatation

- type II very favorable prognosis (96%)

- type III less favorable outcomes (66%)

History and etymology

The word achalasia stems from the Ancient Greek term for "does not relax".

Differential diagnosis

A number of entities may mimic achalasia, forming the so-called 'achalasia pattern'.

- achalasia: the distal segment of narrowing is <3.5 cm

- central and peripheral neuropathy

- scleroderma: gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ) will be open; less severe dilatation

- esophageal malignancy or gastric carcinoma: commonly referred to as pseudoachalasia

- esophageal stricture

- Chagas disease

- anti-Hu antibodies from lung cancer (paraneoplastic syndrome)

Other esophageal disorders should also be considered:

Siehe auch:

- Sklerodermie Ösophagus

- Ösophaguskarzinom

- Pseudoachalasie

- Adenokarzinom des Magens

- Hypomotile Achalasie

- chagas disease

- Ösophagusstrikur

- maligne Ösophagustumoren

- Achalasie in der Thoraxübersicht

- cricopharyngeale Achalasie

- Achalasie Stadien nach Brombart

- Hypermotile Achalasie

- Triple-A-Syndrom

- Supportlevel bei Achalasie

- Ösophaguskarzinom bei Achalasie

- Achalasie bei Kindern

- Achalasie und Hiatushernie

und weiter:

- prästenotische Dilatation

- Esophagus

- Systemische Sklerodermie

- Wandstarre unterer Ösophagus

- Ösophagusstenose

- Dysphagie

- gastrointestinale Manifestationen Sklerodermie

- Störungen der ösophagealen Peristaltik

- Candida Ösophagitis

- epiphrenisches Divertikel

- fehlende Magenblase

- foamy oesophagus sign

- rat-tail sign

- Lisker-Garcia-Ramos-Syndrom

- sigmoid type achalasia associated with ulcer

- bird-beak sign

- american trypanosomiasis

- unspezifische oder nichtklassifizierbare Motilitätsstörungen des Ösophagus

- trypanosomiasis

- Erweiterung Ösophagus

- posttraumatic achalasia

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Achalasie:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Achalasie: