Tuberculosis (pulmonary manifestations)

Pulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis are varied and depend in part whether the infection is primary or post-primary. The lungs are the most common site of primary infection by tuberculosis and are a major source of spread of the disease and of individual morbidity and mortality.

A general discussion of tuberculosis is found in the parent article: tuberculosis; and a discussion of other mycobacterial infections of the lungs is found here: pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infections.

Clinical presentation

The primary infection is usually asymptomatic (the majority of cases), although a small number go on to have symptomatic hematological dissemination which may result in miliary tuberculosis. Only in 5% of patients, usually those with impaired immunity, go on to have progressive primary tuberculosis.

Patients with post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis are often asymptomatic or have only minor symptoms, such as a chronic dry cough. In symptomatic patients, constitutional symptoms are prominent with fever, malaise, and weight loss. A productive cough which is often blood-stained may also be present .

Occasionally patients may present with massive hemoptysis due to an erosion of a bronchial artery .

Clinical presentation in AIDS patients

Patients with AIDS demonstrate altered patterns of infection depending on their CD4 count. When CD4 count drops to below 350 cells/mm pulmonary manifestations appear similar to run-of-the-mill post-primary infections (see below). When CD4 counts drop below 200 cells/mm then the pattern of infection is more likely to resemble primary infection or miliary tuberculosis . Nodal enlargement is also common at this stage.

Pathology

Location

The location of infection within the lung varies with both the stage of infection and age of the patient:

- primary infection can be anywhere in the lung in children whereas there is a predilection for the upper or lower zone in adults

- post-primary infections have a strong predilection for the upper zones

- miliary tuberculosis is evenly distributed throughout both lungs

Radiographic features

Radiographic features depend on the type of infection and are discussed separately.

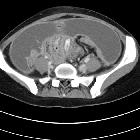

Primary pulmonary tuberculosis

In primary pulmonary tuberculosis, the initial focus of infection can be located anywhere within the lung and has non-specific appearances ranging from too small to be detectable, to patchy areas of consolidation or even lobar consolidation. Radiographic evidence of parenchymal infection is seen in 70% of children and 90% of adults . Cavitation is uncommon in primary TB, seen only in 10-30% of cases . In most cases, the infection becomes localized and a caseating granuloma forms (tuberculoma) which usually eventually calcifies and is then known as a Ghon lesion .

The more striking finding, especially in children, is that of ipsilateral hilar and contiguous mediastinal (paratracheal) lymphadenopathy, usually right-sided . This pattern is seen in over 90% of cases of childhood primary TB, but only 10-30% of adults . These nodes typically have low-density centers with rim enhancement on CT . Occasionally these nodes may be large enough to compress adjacent airways resulting in distal atelectasis .

Pleural effusions are more frequent in adults, seen in 30-40% of cases, whereas they are only present in 5-10% of pediatric cases .

As the host mounts an appropriate immune response both the pulmonary and nodal disease resolve. Calcification of nodes is seen in 35% of cases . When a calcified node and a Ghon lesion are present, the combination is known as a Ranke complex.

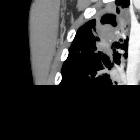

Post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis

Post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis, also known as reactivation tuberculosis or secondary tuberculosis occurs years later, frequently in the setting of a decreased immune status. In the majority of cases, post-primary TB within the lungs develops in either :

Typical appearance of post-primary tuberculosis is that of patchy consolidation or poorly defined linear and nodular opacities .

Post-primary infections are far more likely to cavitate than primary infections and are seen in 20-45% of cases. In the vast majority of cases, they develop in the posterior segments of the upper lobes (85%). The development of an air-fluid level implies communication with the airway, and thus the possibility of contagion. Endobronchial spread along nearby airways is a relatively common finding, resulting in relatively well-defined 2-4 mm nodules or branching lesions (tree-in-bud sign) on CT .

Hilar nodal enlargement is seen in only approximately a third of cases . Lobar consolidation, tuberculoma formation, and miliary TB are also recognized patterns of post-primary TB but are less common.

Tuberculomas account for only 5% of cases of post-primary TB and appear as a well defined rounded mass typically located in the upper lobes. They are usually single (80%) and can measure up to 4 cm in size. Small satellite lesions are seen in most cases . In 20-30% of cases, superimposed cavitation may develop.

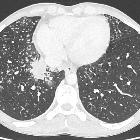

Miliary pulmonary tuberculosis

Miliary tuberculosis is uncommon but carries a poor prognosis. It represents haematogenous dissemination of an uncontrolled tuberculous infection. It is seen both in primary and post-primary tuberculosis. Although implants are seen throughout the body, the lungs are usually the easiest location to image.

Miliary deposits appear as 1-3 mm diameter nodules, which are uniform in size and uniformly distributed . If the treatment is successful, no residual abnormality remains.

Tracheal and bronchial involvement

Isolated tracheal infection by tuberculosis is rare but reported and typically results in irregular circumferential mural thickening. It is usually the result of a contiguous inflammation from adjacent nodal involvement .

Broncholith

A broncholith is a relatively uncommon presentation which is due to erosion of a calcified lymph node into a bronchus, resulting in calcified material entering the lumen. Rarely this material can be coughed up (known as lithoptysis) .

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment is usually only in the setting of progressive primary tuberculosis, miliary tuberculosis, or post-primary infection, and in general primary infections are asymptomatic. For a general discussion please refer to the parent article: tuberculosis.

Administration of protracted courses of multiple antibiotics tailored to the sensitivity of the infective strain is the cornerstone of treatment.

Any patient with tuberculosis should be considered infective until sputum assessment is performed, and patients should be placed in respiratory isolation. In many countries, it is a reportable disease, and contact tracing will be performed.

Additional targeted therapies may be necessary for the setting of empyema, mediastinal complications, or hemoptysis.

It is also important to be aware of historical treatments for pulmonary tuberculosis that may still be seen incidentally radiographically nowadays, such as plombage, thoracoplasty, or oleothorax.

Some patients may show a paradoxical reaction on imaging.

Complications

Recognized complications include:

- the colonization of cavities by fungus, e.g. aspergilloma

- bronchiectasis

- arterial pseudoaneurysms

- bronchial artery pseudoaneurysm

- pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm/Rasmussen aneurysm

- empyema - tuberculous empyema

- fibrothorax

- bronchopleural fistula

Differential diagnosis

The imaging differential is dependent on the type and pattern of infection; consider:

- differential of miliary pulmonary opacities

- differential of alveolar pulmonary consolidation

- differential of a pulmonary cavity

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu pulmonale Tuberkulose:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu pulmonale Tuberkulose: