Brain metastases

Brain metastases are estimated to account for approximately 25-50% of intracranial tumors in hospitalized patients. Due to great variation in imaging appearances, these metastases present a common diagnostic challenge which can importantly affect the management approach for individual patients.

This article will discuss metastatic lesions affecting both the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brainstem parenchyma. For other intracranial metastatic locations, please refer to the main article on intracranial metastases.

Terminology

The term brain technically includes the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brainstem. As the cerebrum corresponds to the majority of the brain volume and thus receives most of its blood supply, it is more common for metastatic lesions to appear in the cerebral parenchyma. Consequently, the term "cerebral metastases" is a synonym for "brain metastases".

Epidemiology

The true incidence of brain metastases is unknown, but recent estimates are as high as 200,000 cases per year in the United States alone .

Five primary tumors account for 80% of brain metastases :

A population-based study of 169,444 cancer patients from 1973 to 2001 in Detroit revealed that overall, 10% of patients diagnosed with one of these five primaries went on to develop brain metastases. Specifically, 19.9% of lung cancers, 6.9% of melanomas, 6.5% of renal cancers, 5.1% of breast cancers and 1.8% of colorectal cancers metastasized to the brain .

Parenchymal blood flow is an important determinant of the distribution of metastases: 80% of metastases localize to the cerebral hemispheres, 15% localize to the cerebellum, and 3% localize to the basal ganglia . Often these tumors can be found at the grey/white matter junction.

Clinical presentation

These patients can commonly present with headaches, seizures, mental status alterations, ataxia, nausea and vomiting, and visual disturbances. However, up to 60-75% of patients can be asymptomatic at the time of imaging .

In patients with known malignancies, the brain can sometimes act as a reservoir for metastatic disease as traditional chemotherapy regimes can have poor permeability through the blood-brain barrier. This can lead to presentation with cerebral metastases, even with quiescent systemic disease.

Pathology

Macroscopic appearance

Typically metastases are relatively well-demarcated from the surrounding parenchyma, and usually, there is a zone of peritumoural edema out of proportion with the tumor size.

Histology

Typically well-demarcated except for melanoma metastases. Their histological appearance will, of course, depend on the primary tumor.

Radiographic features

There is variability in the appearance of these tumors, which can make it challenging to evaluate these lesions on cross-sectional imaging.

Although cerebral metastases are often thought of as being multiple, ~50% are seemingly solitary at diagnosis and in a minority of cases, no known or identifiable malignancy is present . They often occur at the grey-white matter junction or in the arterial watershed areas.

It is known that certain malignancies are more susceptible to hemorrhage and it is important to remember this characteristic when suggesting the diagnosis. Metastases that hemorrhage includes melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, thyroid cancer, lung and breast cancers.

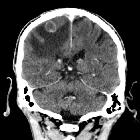

CT

Often the first line of imaging, contrast-enhanced CT was previously thought to be equivalent to MRI for the detection of metastases. However, current MRI technology has been shown to be more sensitive than CT and is the preferred imaging of choice. In any case, there is no evidence that MRI-based screening improves outcomes when compared to contrast-enhanced CT yet so many institutions continue to employ CT as the initial test of choice.

On pre-contrast imaging, the mass may be isodense, hypodense or hyperdense (classically melanoma) compared to normal brain parenchyma with variable amounts of surrounding vasogenic edema. Following administration of contrast, enhancement is also variable and can be intense, punctate, nodular or ring-enhancing if the tumor has outgrown its blood supply.

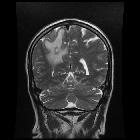

MRI

- T1

- typically iso- to hypointense

- if hemorrhagic may have intrinsic high signal

- non-hemorrhagic melanoma metastases can also have intrinsic high signal due to the paramagnetic properties of melanin

- T1C+

- enhancement pattern can be uniform, punctate, or ring-enhancing, but it is usually intense

- delayed sequences may show additional lesions, therefore contrast-enhanced MR is the current standard for small metastases detection

- T2

- typically hyperintense

- hemorrhage may alter this

- FLAIR

- typically hyperintense

- hyperintense peri-tumoral edema of variable amounts

- DWI/ADC

- edema is out of proportion with tumor size and appears dark on DWI

- ADC demonstrates facilitated diffusion in edema

- MR spectroscopy

- intratumoral choline peak with no choline elevation in the peritumoural edema

- any tumor necrosis results in a lipid peak

- NAA depleted

Nuclear medicine

FDG PET

Generally considered the best imaging tool for metastases. However it can only detect metastases up to 1.5 cm in size, therefore contrast MRI remains the gold standard to rule out small metastases. Lung, breast, colorectal, head and neck, melanoma and thyroid metastases are usually hypermetabolic. Mucinous adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma are typically hypometabolic, and gliomas and lymphomas are variable. Any central hypometabolism indicates necrosis.

PET/CT

May overcome some of the shortcomings and has been shown to possess higher sensitivity in detecting metastases, partly due to hybrid imaging part CT. It may even demonstrate asymptomatic metastases in patients examined for extracranial disease. However, MRI remains gold-standard .

Treatment and prognosis

Symptomatic treatment

Corticosteroids are given to limit the effects of peritumoural edema. Hyperosmolar agents (e.g. mannitol) can be given to decrease ICP and anticonvulsants are given to prevent seizures. Recently, methylphenidate and donepezil have been used to improve cognition, mood, and quality of life.

Therapeutic treatment

Radiation (whole brain external beam or stereotactic for smaller masses), chemotherapy and surgical resection are done to prolong survival and palliate symptoms. Other than germ cell tumors, leukaemias and lymphomas, palliation is the rule and curative therapy is the subject of case reports.

Prognosis

Overall patients with brain metastases typically have a mean survival of one month without treatment. With treatment, survival improves, but it is still dismal. The mean age of survival is still less than one year, although in some patients with solitary metastases longer survival is encountered.

A 2016 trial showed that whole-brain radiation therapy did not improve the overall survival for those patients with a limited number of brain metastases, and was associated with more cognitive impairment .

Differential diagnosis

General imaging differential considerations include:

- primary brain neoplasm especially glioblastoma

- NAA present to a degree

- epicenter on white matter

- extends to ependymal surface

- cerebral abscess

- central restricted diffusion

- dual rim sign

- smooth complete low-intensity rim on SWI

- subacute stroke

- gyriform enhancement typical

- vascular territory

- meningioma

- usually obviously extra-axial

- homogeneous enhancement

- dural tail

- post-treatment effects (post-surgical or post-radiation) hypermetabolic acutely progressing to hypometabolic over time

Siehe auch:

- Meningeom

- Glioblastoma multiforme

- Hirnabszess

- Oligodendrogliom

- Balo concentric sclerosis

- Apoplex

- Tumefaktive Multiple Sklerose

- zystische Hirnmetastasen

- zerebrale Venenthrombose

- eingeblutete zerebrale Metastasen

- Strahlennekrose

- low-grade astrocytoma

und weiter:

- Tumoren der Hypophysenregion

- Neurozystizerkose

- Neurosarkoidose

- Pinealiszyste

- butterfly glioma

- Tuberkulose des ZNS

- Pituitary MRI (an approach)

- Neurotoxoplasmose

- Metastase

- Konzentrische Sklerose Baló

- Lobärblutung

- Dural-Tail-Zeichen

- Hirntumoren

- zerebrale Läsionen mit ringförmiger Kontrastmittelanreicherung

- intraventrikuläre Neoplasien und Läsionen - Überblick

- Subependymom

- bull's eye sign

- Hirnmetastasen Malignes Melanom

- Organmetastasen

- intraaxial

- target sign in brain metastases

- suprasellar / hypothalamic lesions

- Tuberkulom des ZNS

- teratoma suprasellar

- cerebellar metastases

- indication for neuroimaging in new onset seizures

- cerebral metastasis: bronchial carcinoma

- MRI appearance of intracranial metastatic melanoma

- cerebral metastases from lung cancer

- brain metastasis - sarcoma

- zerebrale Metastasen bei Nierenzellkarzinom

- cerebral metastasis (colorectal)

- Hirnmetastasen bei Kolonkarzinom

- Gallengangskarzinom Hirnfiliae

- cerebral metastases - breast primary

- multiple calcifying pseudoneoplasms of the neuraxis (MCAPNON)

- zerebrale Metastasen kolorektales Karzinom

- Metastasen im Pons

- Metastasen in der Hypophyse

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Hirnmetastase:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Hirnmetastase: