dural arteriovenous fistula

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVF) are a heterogeneous collection of conditions that share arteriovenous shunts from dural vessels. They present variably with hemorrhage or venous hypertension and can be challenging to treat.

Epidemiology

Most dural arteriovenous fistulas present in adulthood and account for 10-15% of all cerebral vascular malformations .

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation is highly variable and depends on the location of the supplying and draining vessels, as well as the presence of complications (see below). Presentations include :

- pulsatile tinnitus

- cranial nerve palsies

- seizures

- orbital symptoms (see caroticocavernous fistula)

- symptoms of venous hypertension

- raised intracranial pressure

- focal neurological deficits

Complications

The likelihood depends on venous drainage (reflected in both the Cognard and Borden classification systems), and not arterial supply.

- hemorrhage

- venous congestion/hypertension and edema

- intracranial hypertension

- spinal myelomalacia

Pathology

Dural arteriovenous fistulas are usually acquired and in most instances are idiopathic . In patients with a documented antecedent cause, most occur as the result of neovascularization induced by a previously thrombosed dural venous sinus (typically the transverse sinus). Other causes include trauma and previous craniotomy. It is likely that at least some patients with apparently idiopathic fistulae had prior asymptomatic thrombosis, particularly as inherited prothrombotic conditions (e.g. antithrombin, protein C, and protein S deficiencies) have been associated with development of dAVFs .

Typically, they are supplied by multiple feeders from arteries that supply the relevant part of the meninges and regional scalp vessels that often give transosseous branches:

- supratentorial and lateral: (external carotid artery)

- middle meningeal artery

- superficial temporal artery (transosseous branches)

- anterior cranial fossa: (internal carotid artery)

- ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic artery

- cavernous sinus: (internal and external carotid arteries)

- posterior cranial fossa: (vertebral and external carotid arteries)

- vertebral arteries (both dural and muscular branches)

- occipital and ascending pharyngeal arteries

Location

- transverse/sigmoid sinus

- most common

- least likely to have retrograde venous drainage

- cavernous sinus (indirect caroticocavernous fistula)

- superior sagittal sinus

- straight sinus

- other venous sinuses

- anterior cranial fossa

- typically only ICA supply due to meningeal supply of this region

- frequently associated with retrograde venous drainage

- tentorium: frequently associated with retrograde venous drainage

Association

Radiographic features

CT

Diagnosis can be difficult on non-contrast CT but should be thought of when an intracranial hemorrhage is in an unusual location or age group. With contrast and particularly CT angiography a diagnosis can often be made if care is taken. Findings that may be evident:

- abnormally enlarged and tortuous vessels in the subarachnoid space, corresponding to dilated cortical vein

- an enlarged external carotid artery or enlarged transosseous vessels

- abnormal dural venous sinuses including arterialization of contrast phase in the affected sinus due to arteriovenous shunting

MRI

Again, the diagnosis can be difficult in patients without retrograde venous drainage, with dilated pial vessels in the subarachnoid space being a potential clue.

In patients with retrograde leptomeningeal venous drainage edema is present in approximately half of the patients, although it may also be seen in patients who do not have retrograde drainage on angiography .

The regions of white matter edema may also enhance . These findings are indicative of an aggressive fistula with a high rate of hemorrhage.

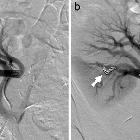

Angiography (DSA)

Catheter digital subtraction angiography demonstrates arteriovenous shunting most typically with multple feeders and with no intervening nidus. DSA remains the gold standard in both diagnosis and accurate classification of dAVF (see below), allowing not only systematic evaluation of feeding vessels (and thus planning for potential intervention) but also demonstrating the presence and extent of retrograde venous drainage. Due to often extensive supply, a six vessel selective angiogram is required (bilateral ICA, ECA and vertebral artery injections).

Classification

A number of classification systems exist. The two most commonly used are :

Both classifications revolve around the knowledge that venous drainage pattern correlates with increasingly aggressive neurological clinical course. The Borden classification is a simplified version of the Cognard system, but loses in granularity .

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment largely depends on the classification of the fistula and the age and comorbidities of the patient, as well as the presence of symptoms directly attributable to the fistula.

- conservative (especially Borden type I and Cognard types I and IIa)

- higher grades (Borden types II and III, Cognard types IIb-V) have an annual mortality rate of ~10% and an annual risk of intracranial hemorrhage of ~8% , so treatment should be considered:

- endovascular

- surgical resection

- stereotaxic radiosurgery

See also

- pial arteriovenous fistula (pAVF)

- vein of Galen aneurysmal malformations (VGAM)

- spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas

Siehe auch:

- Arteria carotis interna

- Sinus sigmoideus

- Arteriovenöse Malformation

- Subarachnoidalblutung

- subdurales Hämatom

- Sinus transversus

- Sinus sagittalis superior

- Sinus cavernosus

- Sinus rectus

- Cognard classification of dural arteriovenous fistulas

- spinale durale arteriovenöse Fistel

- intrakranielle vaskuläre Malformationen

- Borden classification of dural arteriovenous fistulas

- Carotis-Sinus-cavernosus-Fistel

- Arteriovenöse Fistel

und weiter:

- zerebrale arteriovenöse Malformation

- Intrakranielle Blutung

- neuroradiologisches Curriculum

- intramedulläre spinale Tumoren

- Varizen der Orbita

- pulssynchrones Ohrgeräusch

- spinal AVM classification

- cerebral malformation

- Blue-rubber-bleb-naevus-Syndrom

- Onyx

- Klassifikation zerebraler vaskulärer Malformationen

- kraniale durale AV-Fistel

- durale AV Fistel Einteilung

- dural arteriovenous fistula: posterior fossa

- Malformationen der duralen Sinus

- spontanes subdurales Hämatom

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu durale AV-Fistel:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu durale AV-Fistel: