Meningeom

Meningiomas are extra-axial tumors and represent the most common tumor of the meninges. They are a non-glial neoplasm that originates from the meningocytes or arachnoid cap cells of the meninges and are located anywhere that meninges are found, and in some places where only rest cells are presumed to be located. Although they are usually easily diagnosed and are typically benign with a low rate of recurrence following surgery, there are a large number of histological variants with variable imaging features and, in some instances, more aggressive biological behavior.

A broad division of meningiomas is into primary intradural (which may or may not have a secondary extradural extension) and primary extradural (rare) . They can also be classified according to the location (e.g. spinal, intraosseous, intraventricular, etc.), by histological variants (e.g. clear cell, rhabdoid, etc.), and by etiology (e.g. radiation-induced, etc.).

Typical meningiomas appear as dural-based masses isointense to grey matter on both T1 and T2 weighted imaging enhancing vividly on both MRI and CT. Some of the variants as mentioned earlier can, however, vary dramatically in their imaging appearance.

This article is a general discussion of meningioma focusing on typical primary intradural meningiomas and the imaging findings of intracranial disease. For spinal and primary extradural tumors refer to spinal meningioma and primary extradural meningioma articles respectively. Many of the histological variants are also discussed separately.

Rarely (e.g. 1-2% of cases ) meningiomas may also arise at ectopic sites (ectopic primary meningioma) such as in head and neck, orbit, nose, paranasal sinus, oropharynx and even places such as the lung.

Epidemiology

Meningiomas are more common in women, with a ratio of 2:1 intracranially and 4:1 in the spine. Atypical and malignant meningiomas are slightly more common in males. They are uncommon in patients before the age of 40 and should raise suspicion of neurofibromatosis type 2 when found in young patients.

Clinical presentation

Many small meningiomas are found incidentally and are entirely asymptomatic. Often they cause concern as they are mistakenly deemed to be the cause of vague symptoms, most frequently headaches. Larger tumors or those with adjacent edema or abutting particularly sensitive structures can present with a variety of symptoms. Most common presentations include :

- headache: 36%

- paresis: 22%

- change in mental status: 21%

Meningiomas may also become clinically apparent due to mass effect depending on their location:

- supratentorial: 85-90%

- parasagittal, convexities: 45%

- seizures and hemiparesis

- sphenoid ridge: 15-20%

- olfactory groove/planum sphenoidale: 10%

- anosmia (usually not recognized)

- Foster Kennedy syndrome

- juxtasellar: 5-10%

- visual field defects

- cranial nerve deficits

- parasagittal, convexities: 45%

- infratentorial: 5-10%

- obstructive hydrocephalus

- cranial nerve deficits

- miscellaneous intradural: <5%

Occasionally transosseous or intraosseous involvement with prominent hyperostosis may result in local mass effect (e.g. proptosis).

Although dural venous sinus invasion and occlusion does occur, it usually occurs very gradually. Therefore most cases of venous invasion are asymptomatic as collateral veins have had time to enlarge.

Pathology

Meningiomas are thought to arise from meningocytes or arachnoid cap cells, which themselves arise from pluripotent mesenchymal progenitor cells, which accounts for the unusual location of primary extradural tumors .

Although the majority of tumors are sporadic, they are also seen in the setting of previous cranial irradiation and of course in patients with neurofibromatosis type II (Merlin gene on Chromosome 22). Additionally, meningiomas demonstrate estrogen and progesterone sensitivity and may grow during pregnancy.

Grading

Grading of meningiomas follows the WHO classification for CNS tumors and includes both usual histological features (e.g. mitotic index) as well as a number of histological subtypes, some of which have been associated with more aggressive behavior :

- grade I: 'benign" (70%)

- transitional meningioma (40%): mixed histology, typically containing meningothelial and fibrous components

- meningothelial meningioma (17%)

- fibrous meningioma (7%)

- microcystic meningioma

- psammomatous meningioma

- angiomatous meningioma *

- secretory meningioma

- metaplastic meningioma

- lymphoplasmacytic-rich meningioma

- grade II: "atypical" (30%)

- clear cell meningioma

- chordoid meningioma

- atypical by histological criteria (29%)

- 4 to 19 mitoses per ten high-power fields

- infiltration into brain parenchyma **

- 3 or more of the following 5 histologic features: necrosis, sheet-like growth, small cell change, increased cellularity, prominent nucleoli

- grade III: "anaplastic" or "malignant" (~1%)

- rhabdoid meningioma

- papillary meningioma

- anaplastic by histological criteria

- obvious malignant features similar to those seen in melanoma, carcinoma, or high-grade sarcoma

- 20 or more mitosis per ten high-power fields

* Hemangiopericytomas were, until 1993, considered angiomatous meningiomas, but in 2007 WHO classification of CNS tumors they were classified as a separate entity under "Other neoplasms related to the meninges". This again changed in 2016 when the classification was updated. Hemangiopericytomas and solitary fibrous tumors of the dura are considered different manifestations of the same disease, listed under "mesenchymal, non-meningothelial tumors" as a single entry.

** It is important to note, when reading older literature, that in the WHO 2007 classification, infiltration into the brain parenchyma of an otherwise "benign" grade I tumor was sufficient to designate it a grade II tumor. As such, the incidence of grade II tumors increased to ~30% .

Macroscopic

In general, there are two main macroscopic forms easily recognized in imaging studies:

- globose: rounded, well defined dural masses, likened to the appearance of a fried egg seen in profile (the most common presentation)

- en plaque: extensive regions of dural thickening

The cut surface reflects the various histologies encountered, ranging from very soft to extremely firm in fibrous or calcified tumors. They are usually light tan in coloring, although again this will depend on histological subtypes.

Radiographic features

In addition to histological variants, many of which have 'atypical' imaging appearances, a number of 'special examples' of meningiomas are best discussed separately. These include:

- burnt out meningioma

- cystic meningiomas

- intraosseous meningioma

- intraventricular meningioma

- optic nerve sheath meningioma

- radiation-induced meningioma

The remainder of this section focuses on more typical imaging appearances of run-of-the-mill meningiomas.

Plain radiograph

Plain films no longer have a role in the diagnosis or management of meningiomas. Historically a number of features were observed, including:

- enlarged meningeal artery grooves

- hyperostosis or lytic regions

- calcification

- displacement of calcified pineal gland/choroid plexus due to mass effect

CT

CT is often the first modality employed to investigate neurological signs or symptoms, and often is the modality which detects an incidental lesion:

- non-contrast CT

- 60% slightly hyperdense to normal brain, the rest are more isodense

- 20-30% have some calcification

- post-contrast CT

- 72% brightly and homogeneously contrast enhance

- malignant or cystic variants demonstrate more heterogeneity/less intense enhancement

- hyperostosis (5%)

- typical for meningiomas that abut the base of the skull

- need to distinguish reactive hyperostosis from:

- direct skull vault invasion by adjacent meningioma

- primary intraosseous meningioma

- enlargement of the paranasal sinuses (pneumosinus dilatans) has also been suggested to be associated with anterior cranial fossa meningiomas

- lytic/destructive regions are seen particularly in higher grade tumors but should make one suspect alternative pathology (e.g. hemangiopericytoma or metastasis)

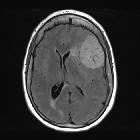

MRI

As is the case with most other intracranial pathology, MRI is the investigation of choice for the diagnosis and characterization of meningiomas. When appearance and location are typical, the diagnosis can be made with a very high degree of certainty. In some instances, however, the appearances are atypical and careful interpretation is needed to make a correct preoperative diagnosis.

Meningiomas typically appear as extra-axial masses with a broad dural base. They are usually homogeneous and well-circumscribed, although many variants are encountered. It seems that the signal intensity of meningiomas on T2-weighted images correlates with the histological subtypes .

Signal characteristics

Signal characteristics of typical meningiomas include:

- T1

- usually isointense to grey matter (60-90%)

- hypointense to grey matter (10-40%): particularly fibrous, psammomatous variants

- T1 C+ (Gd): usually intense and homogeneous enhancement

- T2

- usually isointense to grey matter (~50%)

- hyperintense to grey matter (35-40%)

- usually correlates with a soft texture and hypervascular tumors

- seen in microcystic, secretory, cartilaginous (metaplastic) chordoid and angiomatous variants

- hypointense to grey matter (10-15%): compared to grey matter and usually correlates with harder texture and more fibrous and calcified contents

- DWI/ADC: atypical and malignant subtypes may show greater than expected restricted diffusion although recent work suggests that this is not useful in prospectively predicting histological grade

- MR spectroscopy: usually it does not play a significant role in diagnosis but can help distinguish meningiomas from mimics. Features include:

- increase in alanine (1.3-1.5 ppm)

- increased glutamine/glutamate

- increased choline (Cho): cellular tumor

- absent or significantly reduced N-acetylaspartate (NAA): non-neuronal origin

- absent or significantly reduced creatine (Cr)

- MR perfusion: good correlation between volume transfer constant (k-trans) and histological grade

- MR tractography: allows the identification of white matter tracts adjacent to the meningioma

- this may aid in preoperative planning for meningioma resection by allowing planning of a safer access route that would result in less residual functional iatrogenic deficits

Helpful imaging signs

A number of helpful imaging signs have been described, including:

- CSF cleft sign, which is not specific for meningioma, but helps establish the mass to be extra-axial; loss of this can be seen in grade II and grade III which may suggest brain parenchyma invasion

- dural tail is seen in 60-72% (note that a dural tail is also seen in other processes)

- sunburst or spoke-wheel appearance of the vessels

- white matter buckling sign

- arterial narrowing

- typically seen in meningiomas which encase arteries

- useful sign in parasellar tumors, in distinguishing a meningioma from a pituitary macroadenoma; the latter typically does not narrow vessels

Edema

More than half of the meningiomas demonstrate a variable amount of vasogenic edema in adjacent brain parenchyma . Correlation between age, gender, tumor size, rapid growth, location (convexity and parasagittal > elsewhere), histologic type, and invasion in the case of malignant meningiomas have been suggested in literature but not yet confirmed. Although in general, the presence of severe adjacent edema is considered more compatible with aggressive meningiomas, in some histologically benign types such as secretory type, edema can be disproportionately larger than the small tumor size.

The underlying mechanism is most likely multifactorial however it has been shown that there is a strong association between the presence and severity of the peritumoral vasogenic edema (i.e. edema index) and expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or expression of CEA and CK .

List of some of the proposed underlying mechanisms are:

- venous stasis/occlusion/thrombosis

- compressive ischemia

- aggressive growth/invasion

- parasitization of pial vessels

- histologic subtype: secretory meningioma

- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): produced within the meningioma that enters the adjacent parenchyma

- expression of CEA and CK

Angiography (DSA)

Catheter angiography is rarely now of diagnostic use but rather is performed for preoperative embolization to reduce intraoperative blood loss and alleviate resection of a tumor. This is especially useful for skull base tumors, or those thought to be particularly vascular (e.g. microcystic variants or those with very large vessels). Particles are favored typically 7-9 days prior to surgery although they are not free of complication, particularly one study showed a high prevalence of complications associated with particles smaller than 45-150 μm, so risks and benefits should be thoroughly assessed .

Meningiomas can have a dual blood supply. The majority of tumors are predominantly supplied by meningeal vessels; these are responsible for the sunburst or spoke-wheel pattern observed on MRI/DSA. Some tumors also have a significant pial supply to the periphery of a tumor.

A well known angiographic sign of meningiomas is the mother-in-law sign, in which the tumor contrast blush "comes early, stays late, and is very dense".

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment is usually with surgical excision. If only incomplete resection is possible (especially at the base of the skull) then external-beam radiation therapy can be used .

The Simpson grade correlates the degree of surgical resection completeness with symptomatic recurrence.

Recurrence rate varies with grade and length of follow-up

- grade I = 7-25%

- grade II = 29-52%

- grade III = 50-94%

Metastatic disease is rare but has been reported .

History and etymology

The term "meningioma" was first introduced by Harvey Cushing, a renowned American neurosurgeon, in 1922 .

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis generally includes other dural masses as well as some location-specific entities.

The main dural masses to consider include:

- hemangiopericytoma

- more aggressive often destroying bone

- extensive peripheral vascularity

- more microlobulation

- dural metastases (e.g. breast cancer)

- for other less common differentials see dural masses

Specific location differentials include:

- cerebellopontine angle

- pituitary region

- base of the skull

In the setting of hyperostosis consider:

- Paget's disease

- fibrous dysplasia

- sclerotic metastases (e.g. prostate and breast carcinoma)

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Meningeom:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Meningeom: