giant cell tumor of bone

Giant cell tumors of bone, also known as osteoclastomas, are relatively common bone tumors and are usually benign. They typically arise from the metaphysis of long bones, extend into the epiphysis adjacent to the joint surface, and have a narrow zone of transition.

Epidemiology

Giant cell tumors are common, comprising 18-23% of benign bone neoplasms and 4-9.5% of all primary bone neoplasms . They almost invariably (97-99%) occur when the growth plate has closed and are therefore typically seen in early adulthood. 80% of cases are reported between the ages of 20 and 50, with a peak incidence between 20 and 30 .

There is overall a mild female predilection, especially when located in the spine. However, malignant transformation is far more common in men (M:F of ~3:1) .

Clinical presentation

Often they are incidentally identified. They may present insidiously with bone pain, soft tissue mass, or compression of adjacent structures. The pathological fracture may result in an acute presentation.

Pathology

Giant cell tumors are believed to result from an over-expression in the RANK/RANKL signaling pathway with resultant hyperproliferation of osteoclasts .

These tumors contain numerous thin-walled vascular channels predisposing to areas of hemorrhage and presumably related to the relatively frequent coexistence of aneurysmal bone cysts found in 14% of cases.

Macroscopic appearance

Macroscopically, giant cell tumors are variable in appearance, depending on the amount of hemorrhage, the presence of a coexistent aneurysmal bone cyst, and degree of fibrosis.

Histology

Microscopically they are characterized by prominent and diffuse osteoclastic giant cells and mononuclear cells (round, oval, or polygonal and may resemble normal histiocytes). Frequent mitotic figures in the mononuclear cells may be seen, especially in pregnant women or those on the oral contraceptive pill (due to increased hormone levels) .

Giant cell tumors are low-grade tumors even in radiologically aggressive appearing lesions. Approximately 5-10% are malignant . Sarcomatous transformation is seen, especially in radiotherapy treated inoperable tumors. Although rare (~5%), lung metastases are possible and have an excellent prognosis. Hence, this entity has been called benign metastasizing giant cell tumor .

It is important to realize that features may be difficult to interpret histologically with a relatively wide histological differential diagnosis (e.g. giant cell reparative granuloma, brown tumor, osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, non-ossifying fibroma, and even osteosarcoma with abundant giant cells) , thus rendering radiology indispensable to the interpretation of these lesions.

Location

They typically occur as single lesions. Although any bone can be affected, the most common sites are :

- around the knee: distal femur and proximal tibia: 50-65%

- distal radius: 10-12%

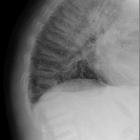

- sacrum: 4-9%

- vertebral body: 7%

- thoracic spine most common, followed by cervical and lumbar spines

Multiple locations: ≈1% (multiple lesions usually occur in association with Paget disease).

Radiographic features

Classic appearance

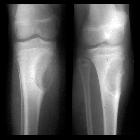

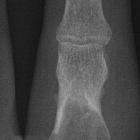

There are four characteristic radiographic features when a giant cell tumor is located in a long bone:

- occurs only with a closed growth plate

- abuts articular surface: 84-99% come within 1 cm of the articular surface

- well-defined with non-sclerotic margin (though <5% may show some sclerosis )

- eccentric: if large this may be difficult to assess

Plain radiograph / CT

General radiographic features include:

- a narrow zone of transition: a broader zone of transition is seen in more aggressive giant cell tumors

- no surrounding sclerosis: 80-85%

- overlying cortex is thinned, expanded, or deficient

- periosteal reaction is only seen in 10-30% of cases

- soft tissue mass is not infrequent

- a pathological fracture may be present

- no matrix calcification/mineralization

MRI

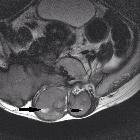

Typical signal characteristics include:

- T1

- low to intermediate signal solid component

- low signal periphery

- solid components enhance, helping distinguish giant cell tumors with an aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) from a pure ABC

- some enhancement may also be seen in adjacent bone marrow

- T2

- heterogeneous high signal with areas of low signal intensity (variable) due to hemosiderin or fibrosis

- if an aneurysmal bone cyst component present, then fluid-fluid levels can be seen

- high signal in adjacent bone marrow thought to represent inflammatory edema

- T1 C+ (Gd): solid components will enhance, helping differentiate from aneurysmal bone cysts

Nuclear medicine

On bone scintigraphy, most giant cell tumors demonstrate increased uptake on delayed images, especially around the periphery, with a central photopenic region (doughnut sign). Increased blood pool activity is also seen, and can be seen in adjacent bones due to generalized regional hyperemia (contiguous bone activity).

Angiography (DSA)

If performed, usually in the setting of preoperative embolization, angiography usually demonstrates a hypervascular tumor (two-thirds of cases) with the rest being hypovascular or avascular.

Treatment and prognosis

Classically, treatment is with curettage and packing with bone chips or polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). Local recurrence is from the periphery of the lesion and has historically occurred in up to 40-60% of cases. Newer intraoperative adjuncts such as thermocoagulation, cryotherapy, or chemical treatment of the resection margins have lowered the recurrence rate to 2.5-10% . Early work on monoclonal antibodies (e.g. denosumab) as an adjuvant treatment targeted at tumor necrosis has shown impressive results . Wide local excision is associated with a lower recurrence rate but has greater morbidity.

Differential diagnosis

There is a relatively wide differential similar to that of a lytic bone lesion:

- chondroblastoma: epiphyseal, usually in skeletally immature patients

- chondromyxoid fibroma: metaphyseal, with a well defined sclerotic margin, multiloculated bubbly appearance

- aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC): younger age group, but may co-exist with giant cell tumor; fluid-fluid levels

- non-ossifying fibroma: usually younger age group

- brown tumor: in the setting of hyperparathyroidism

- enchondroma: only really a consideration in lesions of small bones of the hand and foot

- haemophilic pseudotumor

- chondrosarcoma: typically older age group

- metastases and multiple myeloma

- intraosseous ganglion cyst

- desmoplastic fibroma

- metaphyseal fibrous defect

See also

Siehe auch:

- nicht ossifizierendes Fibrom

- Enchondrom

- Aneurysmatische Knochenzyste

- Chondrosarkom

- Lucent/lytic bone lesion - differential diagnosis (mnemonic)

- intraossäres Ganglion

- Multiples Myelom

- primärer Hyperparathyreoidismus

- Chondroblastom

- Riesenzelltumor

- Renale Osteodystrophie

- Chondromyxoidfibrom

- desmoplastisches Fibrom

- Riesenzelltumor der Sehnenscheiden

- Ostitis fibrosa cystica

- Riesenzelltumor des Sakrums

- Osteoklastom

- Riesenzelltumor der Wirbelsäule

- Metastasen

- Riesenzelltumor des Schädelknochens

und weiter:

- radiologisches muskuloskelettales Curriculum

- Knochentumoren

- teleangiektatisches Osteosarkom

- metaepiphysis

- differential diagnosis for metatarsal region pain

- Läsionen des Sakrums

- Riesenzelltumor Fingerknochen

- contiguous bone activity

- Riesenzelltumor Mittelhandknochen

- Riesenzelltumor des Beckenknochens

- Riesenzelltumor der Patella

- Riesenzelltumor distales Femur

- giant cell tumour in children

- Osteolyse der Tibia

- giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath of the hand

- hyperdense pulmonale Raumforderungen

- giant cell tumor in distal femur

- distribution of giant cell tumour of bone

- Tumoren der Zehen

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Riesenzelltumor des Knochens:

Assoziationen und Differentialdiagnosen zu Riesenzelltumor des Knochens: